Childhood for barbed wire – Gatchinskaya Pravda

Organized by the Nazis in June 1942, a labor camp for children of different age groups – from three to fourteen years old, was opened in the village of Zasitsa in the territory of the pre -war pioneer camp Bonfire, belonging to the Leningrad sewing factory named after Volodarsky. It was located on Lieutenant Schmidt Street, and, on the contrary, across the Oredezh River, was the temple of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God. The Germans called the camp an orphanage or a shelter, in fact, it was a real children's labor concentration camp, surrounded by a fence and spitting wire sections.

Childhood for barbed wire

Here, children were forcibly kept, expelled by the Germans from villages and cities located in the frontline under Leningrad. Only a whole kindergarten was brought from the village of MGA-60 children of five to six years old. Camp buildings included: a two -story building of the pre -revolutionary building, serving the corps (houses for personnel, commandant and security), paramedic infirmary, kitchen, storage facilities and huts, one of which was specially adapted for “infants”. Closer to the river was a bathhouse.

The conditions of the detention were unbearable: older children forced to work, young prisoners died from overwhelming labor, hunger, cold, disease, humiliation and other deprivation. The names of many of them are not established. Children were buried in random mass graves: in the camp, in the surrounding forest in the so -called camp cemetery, next to the village cemetery. The surviving evidence of eyewitnesses give a terrible and incredible picture of the life of small slaves with their cruelty.

Recalls a resident of the village of Zasitsa Nina Ivanovna Dubinina, born in 1933:

“In Vyritsa, to the children's concentration camp, the invaders took place children from all over the Leningrad Region. We got there with my brother. Older guys from morning till night worked in the fields of the former state farm Volodarsky – they laid beds, collected stones. Often, children were kicked into the forests in the vicinity of the outskirts and forced to collect garbage.

The camp overseers were from the locals, the authorities were Germans. They punished little prisoners for any fault. Once she pulled her trough to eat-my hand in her hand. Another time, the girls come running: Nina, your brother was tied to a booth on a chain. It turns out that he, playing, quarreled with another boy and … bit the offender. Once they bite, the “teachers” reasoned, let, like a dog, sits on a chain. This is in two years! Byphal persuaded the senior overseer to free the baby. At eight years old, I managed to get food for my brother, otherwise he would not have survived. They fed camp children with a staggers from a tournament, a balland made of overfected flour – a low -eaten glue for the stomach.

Our mother was engaged in hard labor during the years of occupation-together with other women, she built the road to the fox-corps, manually driving heavy wooden chocks into the ground.Once the whole mountain of these churok covered her, collapsing from a truck – after the war it will come to a heavy injury to the spine and with complete immobility for six years long … Dad died at the front for a single -top thirty years. Shortly before the release of the outskirts, my mother stole me from the camp first, and then her brother. Next to our house, she dug up the trench ahead of time, where we were hiding, and spent the night, prepared a non -sufficient food – it was in the fall. From above, the trench was covered with a huge painting “Ninth shaft” by Aivazovsky, pre-war decoration of our home, long ago thrown out by the invaders to the street.

But, in the end, the Germans still tracked us down, grabbed and took us to the Baltic states. After the release, we returned back to our native Veritsa for a whole week – without money, clothes, food. In the village council, the mother issued temporary documents, and she had to celebrate them every two to three months. As we were not called there! German henchmen and worse … you wash yourself with bitter tears and live on … It was impossible to talk about the experience. The theme of children's hell has become forbidden for many years. ”

From the memoirs of G.G. Levchenko, in the girlishness of Ivanova, born in 1929:

“In September 1942, our family: Mother, Ivanov Elizavet Lavrentievna, and us, four children: Galina, Nina, Alexander and Paul – was forcibly taken from the Mginsky district and sent to the children's camp in the village. Zasitsy. The camp was surrounded by barbed wire and fence, there was a forest around. We were warned that the execution of the camp was relieved. From the age of ten we were driven to work in the fields, in the forest, in the vegetable store in the territory of the former state farm. Volodarsky. They fed a stew from the tournament. Sometimes a doctor came, made us injections with an unknown purpose …

From the memoirs of V.K. Dedova, in the girlhood of Chepp, born in 1928:

“We, three sisters – me, Lida and Nina – were brought to the Vyritsky children's camp in September 1942. The Germans first gathered us in MGA, then they loaded everyone into the train and brought to Gatchina, and then on trucks – to the outskirts. On the territory of the camp there was a two -story house and several huts. The infants were mostly dying, especially those who were without parents. We worked in the forest and in the fields with a lithuanian warder. The German, whose name was Bruno, walked with a whip and cruelly punished for disobedience …

From the memoirs of Valentina Gavrilovna Belisenkova, born in 1932, pre -war resident of the Tosnensky district:

“From the native village, in fact, from the front, on September 16, 1942, the Germans took us out of the mother and four children – to Vyritsa, to the children's forced labor. All the guys are “small less”: I am ten years old, brother Semyon – nine, Nadia – four years old, Tanya – year. And the Nazis and the family did not let his father with his brother did not let go of – forced to distill cattle in Tosno. In the orphanage, the elders were sent to work: we harvested, drove firewood from the forest, weeded carrots, beets, and tournament in the summer.They peeled potatoes in the kitchen for the whole camp, but they did not have the right to eat anything. We were fed from hand to mouth. True, they were forced to pray – in the morning and in the evening, before and after meals. Mom worked on the farm and lived opposite, across the river. I was desperate, I was brave – I ran away to her many times, for which I was punished mercilessly. Once I spent a day with rats in a stoker.”

According to former prisoners of the labor camp, most of the female teachers assigned to the children were local residents. Most often, they tried to somehow alleviate the suffering of children and their mournful fate. The children of the cook, nannies and paramedic, who had their own children in the camp, especially remembered. Some of the guards became famous for their cruelty.

The commandant of the camp was the Austrian officer Del Fabbro, his assistant was the Russian Maria Kukushkina. In 1946, by the decision of the military tribunal, she received 25 years. Among Del Fabbro's closest assistants were also Vyritsa women – Tamara and Vera. Vera was famous for her cruelty, often punishing children. Many years later, she was accidentally met on the train by a former prisoner, nicknamed Lesha the partisan, a boy who more than once received 25 blows from her with rods. During labor duties, Lesha “stole” small potatoes and other vegetables that he collected for younger pupils. Seeing and recognizing his executioner, he called the police. Vera deservedly was given 10 years in the camps. The commandant himself was captured by our troops during the retreat of the Nazis in the Baltic. He was tried as a war criminal in Leningrad. Some employees of the children's camp after the war were summoned to court as witnesses.

Little slaves who reached the age of 10 had to go to work six days a week. Like adults, they worked in the field, sorted out potatoes in a vegetable store, picked mushrooms and berries in the forest, sawed and chopped firewood, and carried water. Berries collected by children: cranberries and lingonberries were sent to Germany, while the prisoners themselves received a portion of gruel and a piece of bread for work. Happiness was when they gave soup from spoiled horse meat. The working day lasted 12 hours.

“Three hundred small prisoners, shaved bald, were placed in a two-story house and neighboring barrack-type buildings,” said Nadezhda Gavrilovna Belezenkova. – Each room accommodated 25-30 children. Few of them survived.

“Mom was allowed into the camp only to breastfeed her younger sister,” one of the prisoners recalled. – But there was not enough milk, and the sister soon died. She was buried outside the camp fence.

In winter, the camp buildings were poorly heated. In some summer rooms, there were no stoves at all.

Leaving the camp was punished, but by hook or by crook, the little prisoners ran away for an hour in the hope of seeing their mothers.

Nadezhda Gavrilovna Belezekova (she was then four years old), recalled how they crawled under the fence, from which it was possible to reach the bridge over the Oredezh by hand. On the other side of the shore, adults lived and worked. The dogs that were assigned to guard the camp did not bark and did not give out children, as they knew each prisoner well. Already after the war, N.G. Belezekova learned that “a woman who lived in the same barracks with her mother regularly “knocked” on the fugitives”, and that thanks to her “efforts”, Nadezhda once almost died in the punishment cell.

Children were punished in a variety of ways: they were beaten with a whip, deprived of lunch, placed in a punishment cell – a cold and damp basement of an old stone building. From more healthy children, the Nazis periodically took blood for their wounded soldiers and officers. As a rule, these children did not survive later … Although, fortunately, this fate has passed for many. According to some prisoners, the children were repeatedly taken somewhere, after which they disappeared.

In the evenings, an ambulance came to the camp, ostensibly for “disinfection”. Former prisoner Alexander Roslov recalled: “In Vyritsa, I sat in a bunker (punishment cell) more than once, when I said the wrong thing, ran the wrong way. I cannot say that they took blood in the camp. But my sister Lena Roslova died there, in the infirmary. She said: “Sasha, take me out of here. I don't even have blood anymore, but they take everything. She was gone the next day.

From the story of Vera Pavlovna Zelenina:

“Heavier was small. They died more often, they were buried behind the fence … Before dinner, the little ones sat by the window that overlooked the kitchen and waited for the next distribution of food. Everyone listened to the exclamation: “They are!” We were punished for the slightest infraction. I remember how, while working on potatoes, we took some potatoes for the kids. When we were returning past the German commandant's office, several Germans came out and began to search us. We were sent to a cold bunker. I remember the horror when we waited: what will happen to us. But they let us go, because we, the workers, were needed. The older children were registered with the German commandant's office, where we were sometimes taken to report. And from the age of fourteen they were already sent to Germany.

Valentin Oskarovich Talyzintsev from Tosno ended up in the Vyritsa camp at the age of nine. When he was 12 years old, he, along with other “strong” teenagers, was selected by the Nazis to be sent by freight train from Siverskaya to Germany, where our boys, like slaves, were bought by local breeders, farmers and even ordinary wealthy German families.

“In Vyritsa there was a kind of transit point: those who were older and stronger were sent to work in Germany,” said V.O. Talyzintsev. – I ended up in Leipzig at a brick and tile factory. Young children, straining themselves, carried trolleys with a load weighing a ton and back. And so every day. It’s impossible to escape – it’s far from home, although some ran away, but they were found nearby and killed on the spot… We were liberated by the Americans in 1945.”

The favorite occupation of the commandant of the Del-Fabbro camp was skiing with troops with bells in the outskirts. Children were very afraid of his appearance. The commandant was taken by the guy Grisha Kuznetsov, one of the senior prisoners of the camp. When they wanted to send Grisha by age to work in Germany, the commandant composed a linden certificate that the boy was dead. And Grisha drove his master almost until the very release of the village. However, the commandant appeared in the labor camp infrequently. Children were very afraid of his appearance and hid when he heard the familiar sounds of a bell. He was strict, always sleek, in a pince -nez, often with a whip in his hand. Next to him was usually the overseer Vera. He conducted some punishments, for example, flogging of guilty boys.

The Germans allowed the local elderly teacher who taught children the basics of diploma. After the war ended, she was accused of aiding the Nazis and called the traitor. She taught children to write and read the camp nanny A.S. Avtonomova, former teacher. At Christmas, the warders forced the children to teach in German a song about the Christmas tree “Oh, Tannenbaum”.

According to eyewitnesses, Elder Seraphim, subsequently the famous Jeroschimon, Serafim Vyritsky, provided significant assistance to the children. He handed over the collected clothes to the little prisoners. On holidays, children, accompanied by adults, in small groups, were released from the camp to the Kazan Temple. They visited the elder Seraphim.

“I well remember how we came to him with the Bethlehem star to congratulate Christmas on January 7th. We, children, were then six or eight people. He was very happy about our arrival. He was lying in a small cell … We were taken to him several times. He saw and knew a lot, told us about the places where he visited, about his life, and probably wanted to console us from fears and return to ordinary things. After all, we children, we did not know anything. He treated us to the fact that someone brought him, and he almost did not eat. ”

About a hundred children's lives were carried away by the typhoid epidemic that happened in the summer of 1943. The camp commandant in a panic announced that if the epidemic does not stop, then the hut will be burned with the children. Risking her life, the camp doctor wrote down incorrect diagnoses and causes of death in the registration journal: injuries of skull, tonsillitis, chickenpox. Several sick children were hidden in the bath. And in the fall of 1943, the epidemic by some miracle really subsided.

“Children's memory has preserved a lot of terrible,” Recalled the former prisoner Valentina Pavlovna Popova, born in 1936. – One epidemic of typhoid, squinting everyone indiscriminately, which is worth it. The sick children were kept in the ward under German woolen blankets. We lie, scattering in a fever (temperature – over forty), and huge lice move in each fold of the bedspread and crawl, crawl. And there is no strength to drive the hated enemy! There was no electricity then, the blankets were ironed with red -hot irons with coal irons.This helped, but not for long, and the insects again crawled out of all the cracks.

An amazing story happened to Nadezhda Petrovna Okulich, who got to the camp at the age of about three years. The girl dying of typhus was adopted by Evdokia Ivanovna Ustinova, a local resident. In some incomprehensible way, she persuaded the Germans to give the emaciated child and left him: “I don’t remember my parents, I only knew that my father was a partisan. When a cry was thrown across Vyritsa that they had brought children, hungry, cold, a woman came to the concentration camp along with other local residents. She brought some food. I don’t know what it seemed to me, but I suddenly jumped out of the crowd of kids: “Mom, mom!” … Before the war, she was a judge, kind, sympathetic, fair. After consulting with relatives, she decided to adopt me …

When my future mother came again, I disappeared. Having searched the whole camp, she found me half-dead … on a mountain of children's corpses – the Germans had thrown out to die. Children have just been taken somewhere, apparently, to take blood. After this procedure I was completely weakened, I could not stand on my feet. And I was hurriedly escorted to the next world. But my mother won me back from death, brought me home in her arms, nursed me for a long time, fed me with a spoon … ” Here, in the camp, the surviving group of children met their liberation.

“Before the retreat in November 1943, the Germans took some of the older children and several large families out of the camp,” recalls V.K. Chepp. – There are 30-40 orphans left, few able-bodied, and several adults with their children. And we were transferred to another room – a small two-story building at the confluence of the Mill stream in Oredezh. This house had a large basement where we hid from shelling before the arrival of our scouts in January 1944. After the liberation of Vyritsa, already in February 1944, rootless children (30 people) were collected and taken to the regional orphanage in Leningrad. At the receiver, they gave us certificates that we were brought from Vyritsa, but they did not say anything exactly where we were under the Germans.

The Nazis tried in any way to confuse the traces of the existence of the children's camp. Children were strictly forbidden to call the orphanage a camp. The fleeing Nazis were afraid of retribution.

“When the Germans retreated, there were 30-50 of us left in the camp, and they all were abandoned. The women who were with us in the camp took custody of us, ”- told Valentina Gavrilovna Belezekova. When Soviet soldiers in January 1944 in white camouflage coats came to Vyritsa, children ran out to meet them – almost the entire adult able-bodied population of the huge village was taken by the Nazis to work in the Baltic states and Germany.

The history of this camp was not forgotten, thanks to the search work organized by the director of Vyritskaya secondary school No. 2 Boris Vasilievich Tetyuev (1915-2004) – a participant in the Great Patriotic War.In 1953, by distribution, he was sent by a geography teacher to work at the Vyritsky school No. 1, and in 1958 he became the director of school No. 2. Since 1960, along with teachers and students of school, he was actively engaged in local history work, which was then not very welcomed and had strict “frames”.

In the spring of 1960, an emergency happened in the village. The river Oredezh, which spilled after the abundant melting of snow, greatly washed the shores, exposing children's skeletons in blurry ground. This happened just in the area of the pioneer camp Bonfire. All this was a direct proof of the existence of a children's concentration camp during the fascist occupation.

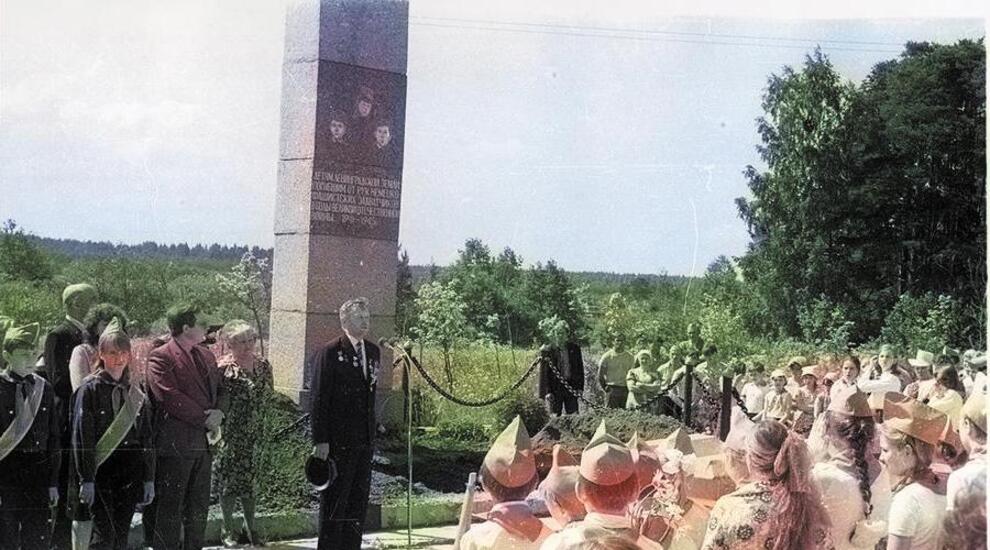

As a result of the search, schoolchildren found out that when in January 1944 the 72nd division liberated the 72nd division, the intelligence officer Petruk discovered in the deserted village of the camp, in which there were still 50 living children, exhausted and patients. Young trackers learned about the whereabouts of more than 200 children's graves. In 1964, at the initiative of the school, administration and deputies of the Vyritsky village council, openings of the remains of children who died in the camp were buried in the camp cemetery were made. All of them were reburied next to the Vyritsky cemetery on the Siberian highway. A memorable “soldier” obelisk was installed on the grave.

On the initiative of the school principal B.V. Tetyuev, teachers and students, in 1974, funds began to raise funds for the installation of a monument on the mass grave of the dead children.

The guys gathered scrap and waste paper, worked on harvesting at the state farm and at a furniture plant, and collected medicinal herbs. As a result, it was possible to collect 40 thousand rubles. At the same time, work began on discussing the project of the future monument to “Children of Leningrad Land”. Several options were proposed.

Created according to the project of the Gatchina artist A.V. Vasilieva, the monument was solemnly opened in 1985.

Far echoes about the children's concentration camp I had to hear from the Vyritsky old -timers. In 1976-1978, I was in the Pioneer camp of the Gatchinsk enterprises DSK and SSK Rainga, which was located on Lieutenant Schmidt Street, next to the pioneer camp “Bonfire”. I was 11-13 years old, but I well remember meetings with war veterans, partisans and local old-timers, which traditionally took place in our camp. Once an elderly man told us about the existence of a children's concentration camp, about which there was no official information about then. We were also shown the place where it was: a two-story ancient, interesting architecture house of pre-revolutionary construction, some other buildings, well-groomed grave mounds in the territory of the Bonfire camp, and also traces of not torn pieces of barbed wire, grown into centuries-old pine trees.

When many years later I visited my native places of my pioneer childhood and visited the updated, still acting Rainbow, there was no longer a neighboring “bonfire”. The camp disappeared, like all its buildings. Everything has changed beyond recognition.In place of the former camp, modern cottages and impregnable fences flaunted …

In 1991, when I was already actively engaged in local history and on a voluntary basis, I headed the work of the People’s Museum in Suid, someone gave my home address (there were no phones at that time) to former minor prisoners of the Vyritsky concentration camp. They came to me in Suida – a small group of elderly women in the hope that I can help them. They needed to confirm the fact of the existence of this camp during the years of the fascist occupation, referring to archival documents. From the KGB and other services they were constantly answered: there is no evidence. This children's camp did not fall on the list among other 359 emergency commission after the end of the war.

It was a summer day. We talked for a long time, sitting on a bench, I tried to show them the path of further search, but I could not help. There were no documentary evidence at my disposal. I was very worried about the fact that I was not able to alleviate the suffering and experiences that fell to the lot of these people. Leaving, they gave me two voluminous notebooks of a large format, which contained their genuine manuscript memories of the children's camp.

Since 1985, traditional meetings of former prisoners of the children's camp began to be held annually in the Vyritsky village library.

In 1993, a special commission was created under the Vyritsky village administration. She was engaged in the collection of information On the children's camp of forced labor created by the Nazi invaders during the Great Patriotic War on the territory of the village of Zasitsa. The chairman of the commission was elected a participant in the Great Patriotic War, retired lieutenant colonel Gennady Matveevich Buzhukov.

The members of the commission did the following work:

1. They interviewed former prisoners of the camp as witnesses caused by the summons of the village council, warning them that they were responsible for the dacha in the prescribed manner, and were convinced that all respondents confirm the fact of stay in this camp.

2. They heard B.V. Tetyueva, who led the search work on the search for evidence of the existence of the Vyritsky children's labor camp.

3. We got acquainted with the collection Children's concentration camp prepared by employees of the Vyritsky village library.

4. They took into account the documentary fact that the commandant of this camp del Fabro was convicted after the war as a military criminal

5. We got acquainted with the original order of the German commandant of the city of Shlisselburg about the forced eviction from the city of the Rodionov family, whose children were imprisoned in the Vyritsky camp.

At their final meeting on November 24, 1993, members of the commission decided:

“The commission considers the existence of forced labor, created by German fascists during the Great Patriotic War in the village of Vyzitsy, in the village of Zasitsy, the village of Zavitsy.In this camp, minor Soviet children were forcibly contained and operated by German invaders. Chairman of the commission Buzhukov G.M., Secretary of the Commission Menshikov G.G.

Thus, only in 1993 was an official document confirming the existence of a children's concentration camp.

. Each year, a very small group of former prisoners of the camp comes to the Oredge shores. Children's memory still haunts them. They lay flowers to the monument to the “children of Leningrad land”. They are now not allowed into the territory of the former camp – it has become private, cottages were built there, and the village library remains the main shelter for former prisoners. They only want one thing: so that their tragedy never repeats again.